I first heard Heinrich Isaak’s choral piece, Innsbruck, ich muß dich lassen, in a Renaissance music history course as an undergrad at Southwestern University. The piece (with the tune in the tenor voice) made me cry. I seem to recall telling my classmates that it was the saddest melody ever written.

Isaak lived from 1450 to 1517, which is roughly from Gutenberg’s invention of the printing press to Luther’s 95 Theses. Not too much is known about Isaak’s life, but we do have at least some of his music, and we have scattered references to his career, here and there. Isaak was so prolific, and so popular and influential in German-speaking lands, that a later writer even called him “Henricus Isaak Germanus.”

Nevertheless, in most of his wills (there were at least four), Isaak refers to himself as “Son of Hugo of Flanders.” Putting the pieces together, he was probably born and educated in Flanders (where music was thriving), and his success allowed him to travel to and work in far-flung places like (what is now) Germany, Switzerland, Italy, and Austria.

And, of course, Innsbruck. We have a letter from 1484 referring to Isaak as a singer for the court of Archduke Sigisimund (of Hapsburg fame) in Innsbruck, and it was here (there?) that he may have written the music that made me cry. There’s some question about whether he actually wrote the melody, but, whether he did or didn’t, he must have found in it the same sadness that I heard in my music history class.

No one knows who wrote the lyrics, though for a long time people believed the author was Maximilian I himself — a nice coincidence, as we are midway through a year of celebrating the 500th anniversary of Maximilian’s death

(12 January 1519). This, in itself, is an interesting development in Austria, which has tended in recent decades to distance itself from its religious past. To some, this celebration of Maximilian and the House of Hapsburg is a recognition of the Catholic tradition entwined in Austria’s history. Then again, Maximilian I broke with tradition and declared himself Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire, instead of being crowned by the Pope.

I like to imagine the unusual Emperor Maximilian as author of this unusual poem. Look at the rhyme scheme: AABCCB.

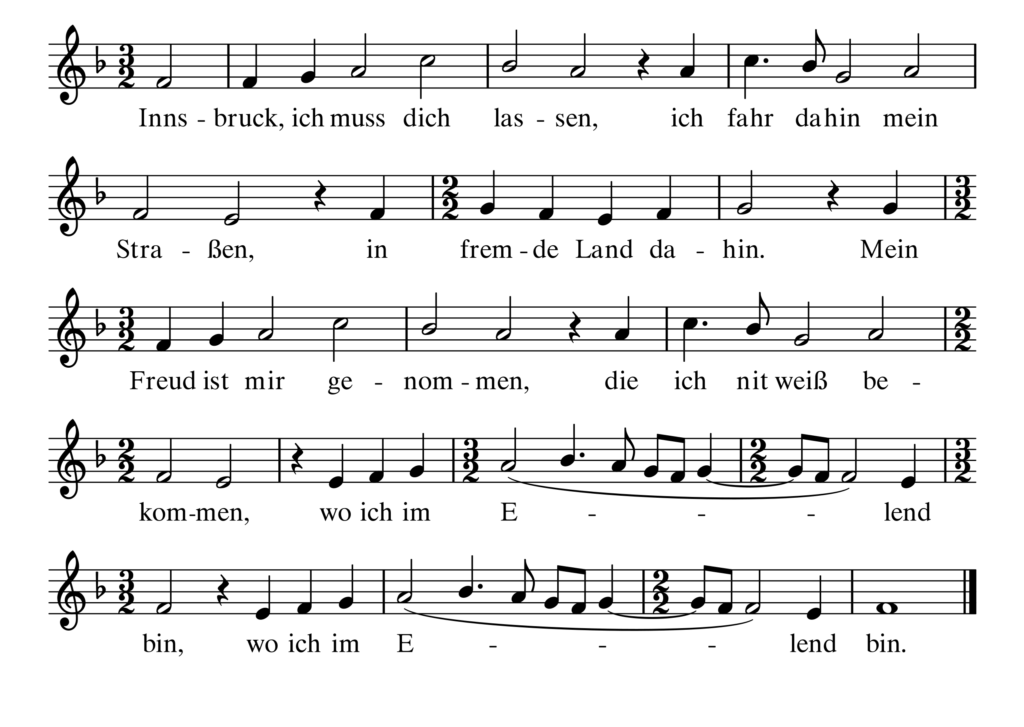

Innsbruck, ich muss dich lassen,

ich fahr dahin mein Straßen,

in fremde Land dahin.

Mein Freud ist mir genommen,

die ich nit weiß bekommen,

wo ich im Elend bin.

Groß Leid muss ich jetzt tragen,

das ich allein tu klagen

dem liebsten Buhlen mein.

Ach Lieb, nun lass mich Armen

im Herzen dein erbarmen,

dass ich muss von dannen sein.

Mein Trost ob allen Weibern,

dein tu ich ewig bleiben,

stet, treu, der Ehren fromm.

Nun muss dich Gott bewahren,

in aller Tugend sparen,

bis dass ich wieder komm.

This AABCCB scheme breaks with tradition, and its structure is reflected in the tune. As a student, I learned about these forms and the music built around them. This tune, in particular, was adopted by the Lutheran tradition to become one of the most beloved of Lutheran chorales. It was so popular, in fact, that people couldn‘t stop writing words for it.

One of the first was Johann Hesse (1490-1547), who wrote a parody (if this word is appropriate here) of the original poem, O Welt, ich muß dich lassen, (except more than three times longer), and these lyrics and others became very popular — partly because Lutherans leveraged the relatively new technology of the printing press to produce songbooks on a previously unknown scale (which, incidentally, more people could actually read).

J. S. Bach was apparently fond of Isaac‘s tune, because it turns up again and again in his music. Set to a poem by Paul Fleming (1609–1640), it became the chorale In allen meinen Taten, the basis for Bach’s famous cantata of the same name (BWV 97). The popularity of the tune with both Lutheran church-goers and composers of Bach‘s stature led to Isaak‘s enduring fame among German composers and musicians, especially in the 19th century. Brahms, for instance, wrote two beautiful chorale preludes for organ on Isaak’s tune (Op. 122, #3, 11). Brahms had pretty high standards when it comes to tunes.

As a music history student I learned that the protagonist of Isaak‘s lament, perhaps a member of the court, is leaving not only Innsbruck but also his love. He promises faithfulness to her, and prays that God will preserve her virtue (Tugend) until he returns.

Perhaps that interpretation works well enough — if you haven‘t been to Innsbruck. On the other hand, standing on a bridge last evening, watching the Inn rushing down from the mountains, feeling those mountains embrace this medieval town — and knowing I’d be leaving tomorrow morning, too— it’s hard not read the poem as personifying Innsbruck herself. As in, die Stadt.

Which brings me back to a little sadness. Innsbruck, I also want you to be the same, when I return.