or

How to save civilization

A title like this prompts us to consider the end of civilization. I recently had a professor tell me that if his section were canceled, it would be the coming of the End of Civilization. My response was that I’d like to offer the section again in the 12-week session, thereby postponing the End of Civilization by a few weeks.

That’s not the End I have in mind.

Rather, I want to talk about the end of civilization in that other sense: end as telos, as in teleology. As in, What is civilization for?

Before we get to that, permit me a brief explanatory digression. Last year, I packaged my central message in the form of a parable about roaches. I was recounting the Parable of the Roaches to one of our esteemed administrators, whose reaction was “I can’t believe you stood up and called your faculty roaches.”

To avoid unpleasantness, let me explain something about parables. Typically, parables aren’t meant to be taken literally. They need interpretation, and that’s a job for the Liberal Arts.

Nevertheless, at considerable hermeneutic risk, I’m going to use the same approach this year. Here, then, is my parable: a pseudo-scientific natural history of our species.

Human history is the story of human beings' penchant for banding together to exclude and avoid interacting with other bands of human beings.

In fact, our species invented language not so much as a means for the transmission of culture or the coordination of group activity, but as a vehicle for talking shit about our neighbors.

It’s a grim pronouncement, but before you judge our species too harshly, consider this: There’s actually a very good evolutionary reason for us to be suspicious of others.

Imagine us, a little band of primates sitting around our favorite watering hole. We see members of another band coming over the hill. We’re anxious; we prepare ourselves for the worst. Why? Because on the Savannah, the odds are pretty high that those other primates are coming to take our stuff. Or worse.

We’ve had a several million years practice at recognizing our band by how we look and act and talk, and being suspicious of other bands who don’t look or act or talk like we do.

But there’s more. In a grand evolutionary irony, it is quite possible that the primary engine of the progress our species has made – using the word ‘progress’ very loosely – is cultural interaction. Let me illustrate.

Imagine our band later that same evening. We gather in our cave to eat our customary dinner of raw centipedes. One of our band says, “You’ll never believe what I saw those stupid, uncivilized primates across the rift doing yesterday! After that big lightning storm, they gathered burning sticks and piled them up to make a little bonfire, and then they actually started roasting their centipedes!”

Now, I ask you to try to imagine — as realistically as you can — the range of reactions among members of our little band. At one end of the spectrum you have this:

“Raw centipedes have a been good enough for our band for countless generations. We are not gonna let those primates across the rift pollute our culture. If we aren’t careful, we’ll all end up like them – a bunch of degenerates eating cooked centepedes.”

Think about that reaction for a moment.

Don’t get me wrong. Obviously, I am not saying that the engine of progress is cultural exchange — happily exchanging ideas for the betterment of everyone. If it were that easy, we couldn’t explain this reaction.

No, I am actually saying that the disruption and dissonance of cultural interaction — that is, when cultures bump and grind against each other — that is the engine. We invent — especially in the symbolic realm — out of a need to reduce anxiety. But in spite of the progress cultural interaction bestows, we’ve spent most of our evolutionary history resisting it.

Here’s another possibility. A year or two passes, and we revisit our little band. The evening conversation has changed. Now, it’s like, “Man, those stupid, backward people across the rift are still roasting centipedes. We’re so much better! We are the ones who invented roasting small rodents.”

What I’m saying here, friends, is that the human condition is not so much fixated on the vivid anticipation of our own mortality. That’s a job for existentialism. No, the human condition is the perpetual anxiety and conflict we feel, because we live somewhere between the guilt of cultural appropriation and the anxiety of realizing that imitation actually is the sincerest, if the least conscious, form of flattery.

But this — is precisely where civilization comes in. I don’t know where we got this idea, but civilization is not a mechanism for achieving ever greater degrees of cultural purity. Civilization is largely about learning to manage the anxiety that results from the inevitable conflict between differing symbolic systems.

Think about the great products of the world’s civilizations. How often does it happen that the greatness of those greats blossoms at times when one culture is grinding up against another?

The moral of that story is that the same Nature who nurtured us — and our fears — on the Savannah, also gave us this big brain that grants us the power to interpret and understand and overcome our fear of each other.

In short, in addition to being H. Alloallergicus, we are also H. hermeneuticus, in one biologically conflicted package.

Or, if you prefer, this big human brain is both the cause and the cure for our anxiety about Otherness. If we worked at it, we could decide to be H. hermeneuticus more often: and that aspiration, my friends, is our mission.

The Liberal Arts can save civilization

How?

Well, what is it that business leaders have (re)discovered about study in the liberal arts? The Liberal Arts are uniquely positioned to teach primates the hermeneutic skills they need to cooperate and be productive, and somehow stay humane while doing it.

As I have frequently quipped, if you need someone who can function well on a team of primates, what’s a better preparation: A MySQL certification, or a close reading of Melville?

And so it falls to us — ACC’s band of Liberal Arts scholars — to rise to the challenge of saving civilization.

We need a blueprint for this mission, a vehicle that will allow us to move forward. And we need a cool name.

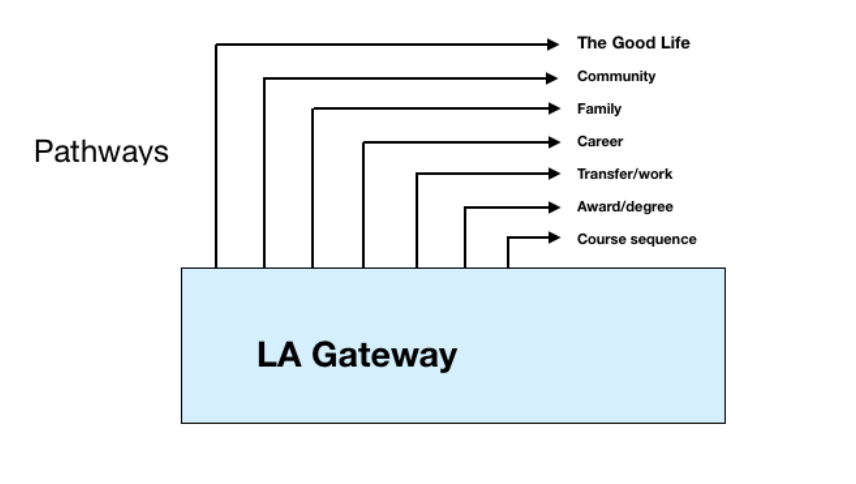

We need a conceptual framework for working toward our aspiration. For this purpose, I’m using notion of a gateway, as in, a gateway into a pathway.

Don’t interpret the term “pathway” in a trivial sense. We have adopted “pathways” at ACC, and that has largely meant relatively superficial changes in the way we shepherd students through our System — for instance, by making degree maps so we know what course comes next.

Those changes and that shepherding are certainly valuable. But there’s a much grander vision of pathways we could adopt – particularly for the grand mission of the liberal arts. So let’s think big — we are after all talking about saving civilization — and let’s ask: What courses would we create in our disciplines if we thought that saving civilization depended on us professing the Liberal Arts?

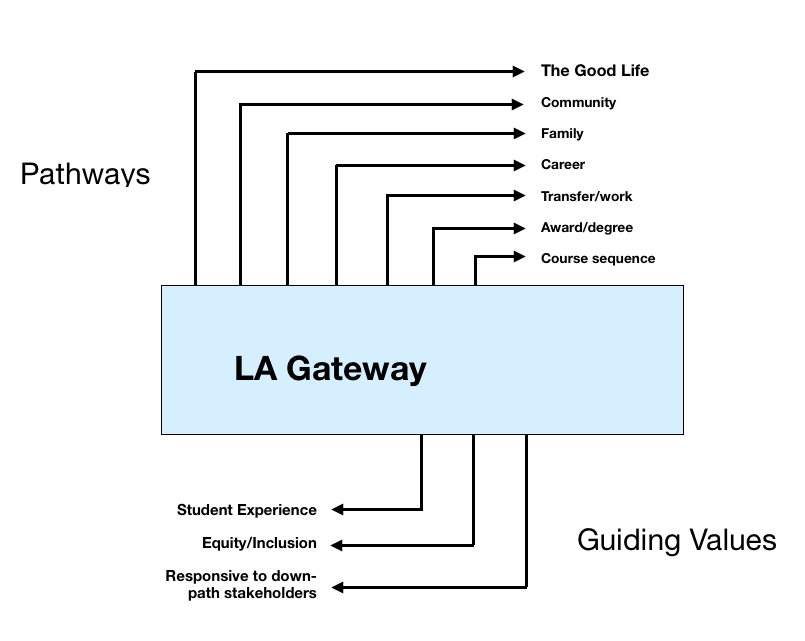

First, think about the student’s pathways in the largest, most encompassing sense: the course, the sequence, the award — transfer or workforce — work life, family, community — and ultimately, the goal of living a Good Life. Yes, you heard right: It’s time to stop apologizing and get our apologetics on: Engagement in the Liberal Arts is, and always has been, about living the best kind of human life.

I’m going to propose boldly that living the best kind of human life simply cannot be a life of whistling in the dark whenever we confront our anxieties about the Other. Living a Good Life is a life of thriving in a genuinely pluralistic society.

Now ask yourself: What courses would we create for our disciplines if the goal of each primate who takes them is to live a Good Life? We would:

- make the student experience central

- cast the largest possible net, and welcome divergent voices and perspectives into the ever-expanding Great Conversation

- anticipate the needs of everyone touched by our students in the future, and build in reflective preparation for those needs

Let those become our guiding values.

We have gone down these paths before our students — which makes us their guides. Inevitably our actions speak as loudly as our lectures, so what face shall we present to them? We are Liberal Arts scholars. We live in disciplines. Our disciplines are little pockets of pluralism, with difference of informed opinion as our daily diet, right?

Yes, and no. We’re also primates, and another way to look at ourselves is that we also band together to exclude other bands. (At Convocation, I asked people to look around their tables at those they had chosen to sit with — and the response was a ripple of nervous laughter.) But in the Liberal Arts, we also fight that urge. We listen. We strive to understand. Or at least, we try — and we fail. But we keep coming back for more.

We are called by the Liberal Arts to embody a certain intellectual humility — the willingness to slow down and listen and understand. But that humility is matched with intellectual courage: The will to try, again and again, to say true things, and to let others hear and disagree. Our calling is a perpetual discipline of learning, reflection, and self-awareness in encounter with Otherness. Think about that: What could possibly be better preparation for thriving in a pluralistic society?

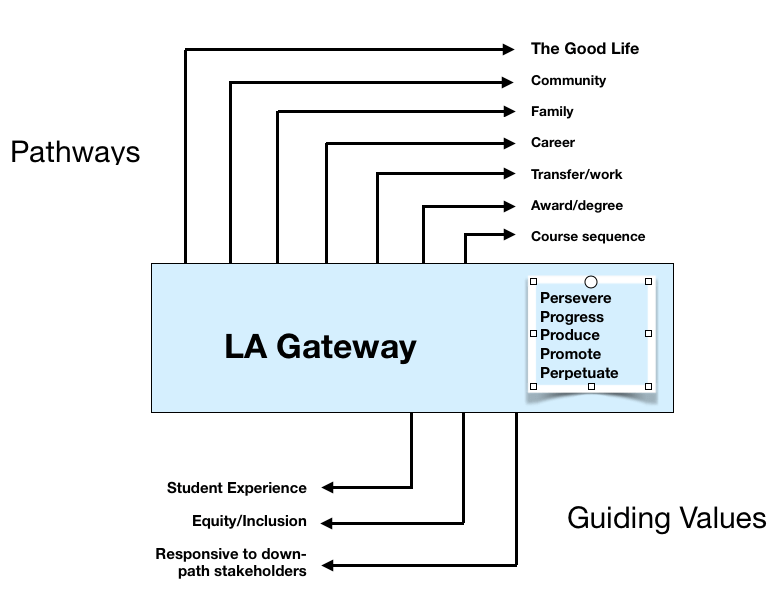

So, we model this self-discipline for our students, and we encourage them to develop these habits of mind:

- Persevere: Don’t give up — in this course, in a conversation, in a line of inquiry, in the pursuit of truth, or in the work of saving civilization.

- Progress: Don’t just be ambulatory! Learn how to gauge progress — benchmarks, indicators, self-reflection, honesty (with yourself, above all). We stand on the shoulders of giants, but give yourself credit for climbing up there to have a look.

- Produce meaningful intellectual work — and challenge yourself to do better work next time.

- Promote the fruits of your work to others — both as a bold attempt to say something true and as an invitation to critique

- Perpetuate these traits, deepen them into habits of mind, and expand them to encompass more and more of your decision-making.

This is the Liberal Arts Gateway: An aspiration, guiding values, and the foundational elements of intellectual character.

But this is just a surface description of the Gateway. Each of you, each discipline needs to penetrate this surface and find deeper principles that drive instantiations of the Gateway. What will this be like for writing? for literature? philosophy? What will it be for ESOL? INRW? CoReqs? Dual Credit? Honors?

And when you ask these questions taking the LA Gateway to heart, you can’t help but ask, What can I find in my discipline for this student to equip, inspire, and empower her or him for living a Good Life? What is my gift to this student’s family? co-workers? community?

Don’t try to dodge responsibility by resorting to the craft and art of your specialization: You are already influencing your students, those families, co-workers, communities. And you are contributing, somehow, to each student’s dream of living a Good Life. How — well, that’s up to you.

Now we’ve come to the exhortation part of my homily. The LA Gateway is a framework for saving civilization, one student’s success at a time, but this is just a roadmap that points all of us in the same direction. We have a lot of work to do to get from the map through the wilderness and within sight of our destination. I challenge you to think about how you would build the course that saves civilization. But don’t stop with a daydream — make a proposal for a Gateway course, and let’s get dirty.

The basic structure is in place. There is a faculty committee, chaired by Arun John, to which you can submit proposals. They will review, give feedback, and make recommendations, with an eye to piloting promising proposals as “gateway courses.” Some ideas are already under development. If you want to know more, be in touch with me or with Arun. In due course, I’ll have more information available.

The good news is that so many of you are already doing great work — let’s join forces and help students progress even more by explicitly articulating how your work fits into their pathways. Striving for excellence should never be a stealth activity.

I’m also challenging departments to empower and encourage professors to think big. Talk openly about excellence and about saving civilization. Lower the cost of failure and give professors space (and the urging) to think bigger — and to fail big. Without the risk of failure, there’s no real progress — or evolution, for that matter. Find ways to open doors for your colleagues, even if, and maybe especially if you disagree with their approaches. If you think about it, that’s another way of living out the Great Conversation.

If my address raises more questions than answers, then I’ve succeeded in prompting you to think about what this Gateway might mean for you and your students. Ask questions, talk to people, and get involved. Those of us who have been working on the Gateway are energized by these ideas, and we are inventing the infrastructure to support it as we go.

Stay tuned — there’s more to come.

Let me end with this: It is not enough to teach students an inventory of possible opinions and beliefs. That’s a bus tour of the liberal arts: Nice, but superficial, and no real preparation for the challenge of encountering the Other. On the contrary, our mission — and the mission of the liberal arts — is to equip students with the hermeneutic skills and knowledge they need to thrive in a pluralistic society. It’s interesting to note that this mission is largely coextensive with the goal of maximizing autonomy in grounded belief formation.

The Liberal Arts is big enough for all of us, but professing the Liberal Arts has always meant walking a fine line between seeking disciples and empowering autonomy — which are other ways of saying “forming bands” and encountering Otherness.

Nietzsche put this tension quite nicely in Also Sprach Zarathustra: “Man vergilt einem Lehrer schlecht, wenn man immer nur der Schüler

bleibt.”

“One repays a teacher badly if one remains only a student.”